What The Tattooist of Auschwitz taught me about separating fact from fiction

Heather Morris followed up her best-selling Tattooist of Auschwitz with a sequel, Cilka’s Journey

Ever since I heard about Heather Morris’ best-seller The Tattooist of Auschwitz , I’ve been fascinated in how she researched her story through countless interviews with her protagonist, Lale Sokolov. She eventually decided to write this story as a novel based on fact.

In an interview she gave with Goodreads, she explained why she decided to write her book as fiction:

“To write the book as a memoir or biography, I would have had to leave out Gita…other than the times she and Lale were together. I wanted to weave their love story into the events, tragedies, and horror that are factually documented from their time in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

“Lale couldn't remember the names of some of the prisoners he interacted with, and I didn't want to refer to them as Prisoner One or Prisoner Two. I wanted to give them names, so the reader could visualize and relate to them as people. I am lucky to have a videotape of Gita talking of her time in the camp. I have also met a friend of hers who was with her in the camp. So, between the video and Gita's friend's stories, I could write about the pain and suffering the girls endured—something I could not have included if writing it simply as Lale's memoir.”

Cilka’s Journey - the sequel

Lale had often referred to Cilka in his interviews saying she was the bravest person he knew and that she saved his life. Morris could see there was another story, but as Cilka had died, she no longer had access to her memory.

Morris needed to find a different way to write Cilka’s story, so travelled to her home country of Slovakia to meet friends who had known her. But Cilka had never shared details of her dark past, so Morris relied on professional researchers and other source material to piece together Cilka’s life in the Gulag, where she ended up after enduring the horrors of Auschwitz.

Heather Morris did most of her research during the day, reading testimonies and other books about the Gulag system. But then she did something remarkable: she threw away the research and began to write.

Heather Morris on writing

In a recent interview in Writing Magazine, Morris described how when it came to focus on the writing, she had no books and no research documents in front of her, “relying on it being clear in my head if it was going to end up on the page.”

In both her books, she had to use her imagination to envisage her characters, how they behaved and what they said. But all the time, she had the backbone of research which gave her the structure she needed to make her writing ring true.

The Hidden Village and research

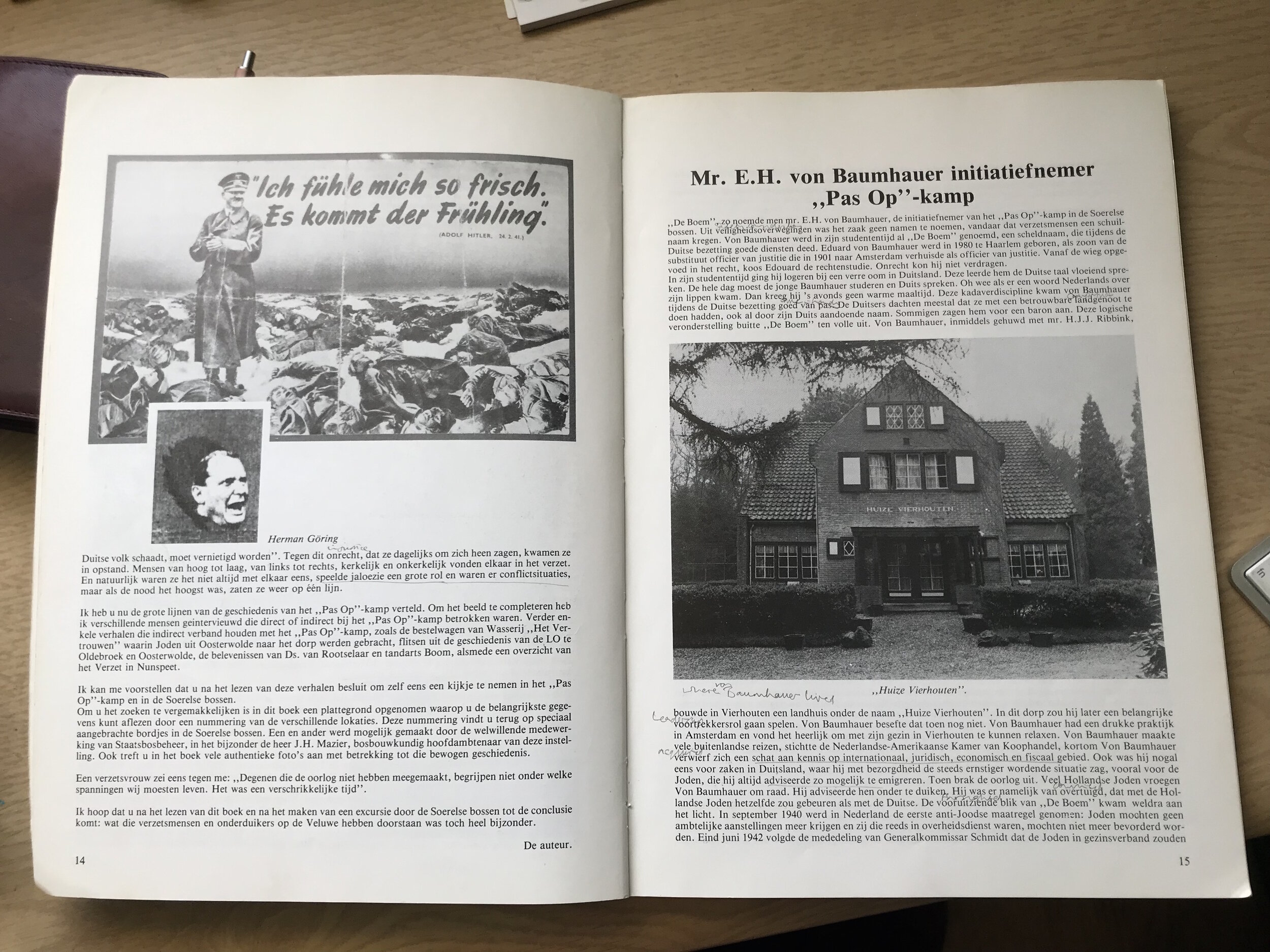

When I was researching the events behind the foundation of the hidden village in the Veluwe woods in Holland, I immersed myself in as much information as I could find, but it was quite limited. It was mostly written in Dutch, naturally, and I spent months poring over difficult texts with the help of Google translate and my imperfect knowledge of the language.

Het Verscholen Dorp, by A. Visser, an inspiring account of the real hidden village in Veluwe, Holland (including translations for words I didn’t understand!)

Like Heather Morris, I also needed to mine my imagination to create the characters that would bring this untold story to life. However, I wasn’t brave enough to throw my research away - I had my notes and source material close at hand to inspire me and ensure the accuracy of what I was writing.

Like The Tattooist of Auschwitz, I used real events and accounts from people who had lived through WW2 to shape my story. It’s not so much about separating fact from fiction as looking for half-told or untold stories and bringing them to life.